In a post I made early last year about the fascinating story of Lieutenant Gilbert Ely, I briefly mentioned an officer named Sidney Burbank. This reference probably meant little to most readers, but I had previously started doing some research on General Burbank for another project and, after re-reading that entry, I decided to share Burbank’s story here. He held higher rank than Gilbert Ely, but, like the Lieutenant, was a largely unknown American soldier, and I think his story is one worth sharing as well.

Sidney Burbank was born in Lexington, Massachusetts on September 26, 1807, the newest member of a military family. He was the son of Lieutenant Colonel Sullivan Burbank, who had been wounded during the War of 1812. Sullivan’s father, Captain Samuel Burbank Jr., had served in the American Revolutionary War, apparently receiving a promotion after the Battle of Bunker Hill.

Sidney attended West Point and graduated seventeenth out of forty-six in the class of 1829, which famously included future Confederate Generals Robert E. Lee and Joseph Johnston, as well as Ormsby Mitchel, who became a Union general and an astronomer who founded the Cincinnati observatory. Burbank ranked second on the class roll of conduct.

He served as a Second Lieutenant in the First Infantry in the 1830s, and returned to West Point as an assistant instructor of tactics. He then fought in the Indian Wars, including the Black Hawk War and the Seminole War. He was promoted to Captain and served in various outposts throughout the west, including Fort Crawford in Wisconsin and Fort Leavenworth in Kansas. In this role, he also helped establish Fort Inge and Fort Duncan, both in Texas. Burbank apparently had no involvement in the Mexican War.

In 1855, he received promotion to Major and in 1859 was appointed as Western Superintendent of Recruiting Services, headquartered at the Newport Barracks in Newport, Kentucky, across the Ohio River from Cincinnati.

Newport Barracks

He remained there until 1861, when he was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel of the 13th Regiment of the U.S. Army on May 14. His new regiment received assignment as the guards at Alton Federal Military Prison in Illinois. This unit was there when it opened and received its first Confederate prisoners in February of 1862.

One small example of his duties occurred on June 4, 1861, when he mustered the First Kentucky Infantry regiment into the U.S. Army at Camp Clay in Pendleton, Ohio, a small Cincinnati neighborhood. At this point, Kentucky was still trying to maintain neutrality in the war, so some Kentucky regiments, both Union and Confederate, organized in neighboring states and many non-Kentuckians joined these units, including the Lieutenant Ely mentioned previously.

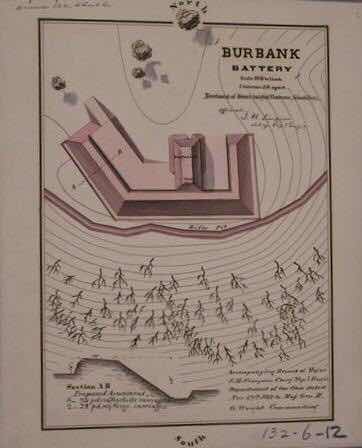

Around this same time, some companies of the 13th Infantry were stationed at Beech Woods Battery (later renamed to Phil Kearney Battery) in Northern Kentucky, not far from the Newport Barracks. Burbank commanded these troops and served as commandant of Cincinnati in September, as the “Siege of Cincinnati” was taking place. One of the local defensive positions guarding against a threatened Confederate invasion, Burbank Battery, was named in his honor. (Ironically, most of the physical defenses of Cincinnati were not in the actual city, but, rather, among the hills of Northern Kentucky, as engineers took advantage of the terrain and the bend in the Ohio River.)

On September 16, he was promoted again, this time to Colonel of the Second Infantry Regiment. In 1863, he led this regiment and others as a brigade commander in the Army of the Potomac. He commanded these troops at the famous battles of Chancellorsville and Gettysburg. Here is his official report from the battle in Pennsylvania, where his forces suffered heavy losses on July 2.

He served in this role until early 1864, but, advancing in age as the war continued, he suffered issues with his health and eyesight. He received less stressful assignments, including responsibility for a draft rendezvous (where drafted soldiers were enrolled into the army) in Columbus, Ohio. He then rejoined the Second Infantry regiment in its headquarters at the Newport Barracks in June of 1864 and remained there until 1866, when the army transferred his command to Louisville.

Before this transfer, he had suffered a great personal loss when his son, Captain Sullivan W. Burbank, died in June of 1864 due to wounds received at the Battle of the Wilderness a few weeks previously. According to Ronald Coddington’s book Faces of the Civil War (2004, Johns Hopkins University Press), at the start of the war Sullivan had asked his father to find him a commission in the army. Sidney succeeded in doing so, but upon learning of his son’s death, felt tremendous guilt and sorrow over his son’s fate, as virtually any father would.

As the previously-mentioned transfer shows, he remained in the army after the war, as a military life was his destiny since birth. In 1866, he received a promotion to Brevet Brigadier General in the regular U.S. Army, effective March 13, 1865. He worked on rebuilding the Second Infantry and served on various boards and positions in these years. His work included recruiting duty and serving as President of the Army Examining Board for candidates to be appointed to the army, a title he received immediately after his transfer to Louisville.

From 1867 to 1869, he was Assistant Commissioner of the Freedman’s Bureau in Kentucky. The Freedman’s Bureau existed to provide assistance to former slaves as they transitioned to freedom, but it faced many challenges in its brief existence, including financial troubles and racism.

Burbank retired from the army in 1870 after forty years of service, and moved back to Newport, living not far from the barracks where he had served. He remained a resident of this city for over a decade, living on Front Street from 1870 until his death in 1882.

In an example of the way the Civil War could affect American families, census records indicate that his wife Isabella (neé Slaughter) was a native of Virginia (as were her parents), though her loyalty surely remained with her husband’s side during the war. It is unknown how or if her family relations existed during and after the war. It is possible her family members were Southern Unionists who supported the Union cause, but perhaps they favored the Confederacy, yet still remained on good terms with the Burbanks. Another possibility is that the family ties broke apart during the war and then reconciled at a later point, but some families, like that of Union General George H. Thomas, another Virginian, saw their family bonds completely destroyed by the long, bitter war.

The Burbanks had three children, including two sons (Sullivan and Clayton) who served in the army, as well as daughter Frances, who married soldier William Maize, adding to the family’s military tradition. Clayton also was stationed in the Newport Barracks in the post-war years.

Sidney Burbank passed away on December 7, 1882 at the age of seventy-five, due to old age and inflammation of the bowels. He left behind an estate valued at just more than $10,800. According to his obituary in the Cincinnati Enquirer, his funeral was a private service at his home, with family and a few military colleagues present. He was laid to rest in a “beautiful casket, with massive silver ornaments.” The lid included a silver plaque with Burbank’s name and birth and death dates on it. His body wore a full Brigadier-General’s uniform, and flowers decorated the casket. He was laid to rest in an unmarked grave in section fourteen of Spring Grove Cemetery in Cincinnati.

Sidney Burbank was a lifelong military man from a military family and led a long and honorable military life, in peacetime and in war.

Rest In Peace, General Burbank.

Lytle Camp 10, Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War arecworing to get him a headstone this year, and conduct a graveside ceremony.

ReplyDeleteBurbank is a distant relative. When will the ceremony be held? Thank you.

DeleteI like Burbank, mostly from his involvement as a regular at Gettysburg. Excellent post, Richard...will you be leading the charge to have his burial site denoted with a government marker? :)

ReplyDeleteHave you set a date? Burbank was a distant relative and there are members of my family who might wish to attend or donate.

ReplyDelete